Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Farmer-herder conflicts in Africa – dynamics and potential solutions

Conflicts between farmers and herders are increasingly coming under the spotlight. For example, in 2018, the African Union Commissioner for Peace and Security Smail Chergui stated that “conflicts between herders and farmers on the continent take more lives than terrorism”, while a 2021 news article in The Guardian describes “violence linked to conflicts between farmers and herders across West and Central Africa has led to more than 15,000 deaths … half of those have occurred since 2018, most of them in Nigeria, which has created the country’s deadliest security crisis.”

Public domain literature often presents the topic with inflammatory language and labelling of particular groups. The Fulani, the largest pastoralist group in West Africa, are referred to as “strangers” or “aliens”, or as a public danger. Often, this group is conflated with known terrorist organisations. The Global Terrorism Index for 2015 claims that Nigeria is home to “two of the five most deadly terrorist groups in 2014; Boko Haram and Fulani militants”, using a catch-all term to describe the Fulani. Additionally, conflict incidents are presented inconsistently, with what is often a cacophony of causes and the farmers referred to as the victims and herders, with their pastoral, mobile way of life, as the assailants. Descriptions of the conflicts can be selective and tailored to particular actions or interventions, such as passing grazing bans to reign in pastoralists’ “indiscriminate grazing”, using degradation narratives to “legitimise and pave the way for agricultural investments and environmental conservation”, using scarcity narratives to justify decisions taken to better manage “underutilised” resources, securitising and politicising climate change by linking climate change-driven migration with violence and insecurity and, perhaps most dangerously, extremist groups and politicians using and manipulating farmer-herder grievances to further their own territorial or political objectives.

Digging to identify the root causes

From 2022, the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), through the Supporting Pastoralism and Agriculture in Recurrent and Protracted Crises (SPARC) project funded by the UK Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office and the CGIAR Initiatives on Fragility, Conflict and Migration, and Livestock and Climate, have been digging deeper into these issues.

As a first step, and in order to better understand what research is saying about farmer-herder conflicts, a systematic scoping literature review was undertaken. The review explored academic and think-tank literature on the root causes of farmer-herder conflicts to uncover any trends and potential gaps in our current understanding. The review was first conducted in English and then in French to ensure the inclusion of as many studies as possible, and the results were combined.

Overall trends in published research

The search in Science Direct showed a marked increase in journal articles produced between 2000 and 2021, with around 10 produced in 2000 and more than 70 produced per year between 2019 and 2022. This confirms the general consensus that interest in farmer-herder conflicts has grown significantly over the last two decades. Ninety-eight per cent of reviewed studies report that farmer-herder conflict is increasing in frequency, intensity, or both. However, most studies mention this as a general statement, and few show it as a research finding. All identified studies concentrate on West Africa and the East Horn of Africa, with the majority focused on West Africa, particularly Burkina Faso, Nigeria and Mali.

Neglect of the gender dimension of conflict has been acknowledged for some time, but still, nearly 20 years later, the role of women in conflict is not sufficiently discussed, particularly women’s roles in promoting conflict or promoting peace. In this review, only 25 of the 88 articles and papers mentioned women in relation to the conflicts described. This suggests a continued gap in research.

Thirty-eight of the 88 publications mention youth, with 81 per cent of the articles/reports describing them as contributors to conflict, 50 per cent as victims and only 18 per cent as peacemakers. Although the studies did not emphasise the aspect, they explicitly referred to young men as being susceptible to recruitment into armed groups, forming vigilante groups for community protection, or tracking and returning stolen livestock, suggesting that the focus was on them and not on young women. No article included any specific description of youth indicating that they were talking about women or girls, pointing to a continued gap in the research. Additionally, we found no stand-alone research on the role of youth in conflict, indicating an area for further research.

While all studies reported land and natural resources conflict, most mention the link as a general statement like conflict or competition over land or water, a combination of the two. A handful of studies provided a deeper analysis. “Climate change” or “changing climate” was mentioned in 62 of the 88 papers (70 %).

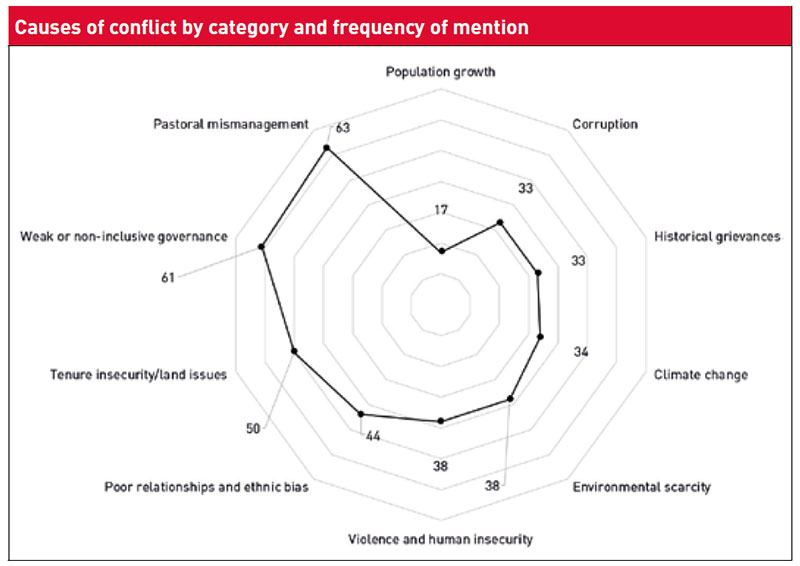

All articles and papers identified multiple causes of farmer-herder conflict, with no paper citing a single cause. The most frequently cited cause categories were pastoral mismanagement, weak or non-inclusive governance, tenure insecurity, land issues, deteriorating relationships and ethnic bias. These were followed by environmental scarcity and violence (see Figure below) . Climate change, while a topic of general interest, did not feature in the top causes. While it is difficult to draw any definitive conclusions from these results, they do suggest that the causes most mentioned focus on governance, political and social factors of conflict rather than the more technical aspects of resource scarcity or climate change. This finding aligns with those from previous reviews. Additionally, the large number of articles that cite pastoral mismanagement as a cause of conflict (63 in all) suggest a simplistic reading of the conflicts that have deeper root causes found elsewhere, as well as likely influence of predominant narratives in the media.

Conclusions and recommendations

While there has been a significant increase in attention given to farmer-herder conflicts over the last two decades, this review identified only a few primary studies. Though studies indicate increasing (or increasingly violent) tension between the two groups, most mention this as a general statement, and few provide robust evidence. This supports those researchers who refute the mantra of increasing conflict and call for more primary research and critical analysis. The review highlights the complex and multi-faceted nature of farmer-herder conflicts that cannot be simplified as one cause or another. Preliminary research from a Sudan local case study on farmer-herder conflicts in Gadarif State (see Box at the end of the article) suggest similar conclusions.

The intricate web of causes suggests that researchers would benefit from a comprehensive framework in which to situate their research and better understand the underlying drivers of specific farmer-herder conflicts. The core elements of this framework are:

- Interconnectedness of causes: Farmer-herder conflicts are rarely driven by a single cause, but rather by a combination of factors that interact with each other at different levels. These causes range from governance issues to environmental changes, historical grievances and cultural biases. A well-structured framework would help researchers map these interconnected causes and visualise how they influence each other, aiding in identifying root causes and potential leverage points for conflict prevention and resolution.

- Contextual understanding: Causes and their effects vary based on geographical, social, political, and cultural contexts. A robust framework would allow researchers to incorporate these contextual variables and develop a nuanced understanding of conflicts that goes beyond generalised narratives.

- Avoiding oversimplification: Oversimplification causes, such as attributing conflicts solely to environmental scarcity or climate change, can hinder accurate analysis and effective solutions. A well-structured framework would discourage such oversimplification and encourage researchers to delve deeper into the underlying structural drivers of conflicts.

- Uncovering hidden stakeholders and causes: There are clear gaps in the research, such as the lack of focus on the roles of women and youth in conflicts and the tendency to overlook certain root causes. A comprehensive framework would prompt researchers to explore these often neglected dimensions of conflicts and encourage more inclusive and holistic analyses.

- Integration of multiple disciplines: Farmer-herder conflicts involve complex social, economic, political and environmental dynamics. A robust framework would encourage interdisciplinary collaboration, allowing researchers from various fields to contribute their expertise and perspectives, thus generating a more complete understanding of the conflicts.

- Guiding research focus: The “cacophony” of causes can be overwhelming for researchers seeking to conduct studies. A well-designed framework would help researchers narrow their focus, guiding them to investigate specific interactions and aspects within the larger web of causes.

- Policy and intervention design: An effective framework would aid researchers, policy-makers, practitioners and organisations working to address farmer-herder conflicts. It would provide a structured approach to designing interventions that target the underlying causes and dynamics rather than merely addressing symptoms.

- Visualising complexity: The complexity of farmer-herder conflicts requires a visual representation to grasp the intricate relationships between causes and effects. A framework can provide a graphical model that facilitates clear communication of research findings to stakeholders and the broader public.

It is now important to use this framework to explore the reasons and causes of farmer-herder conflicts in more detail, without using the inflammatory language and labelling of specific groups described in the introduction. Only by doing this can we begin to understand the problem in a clearer and fairer way.

Causes and impacts of farmer-herder conflicts through a political economy and food production lens.

Case study in Gadarif State, Sudan

Gadarif State is located in eastern Sudan and is home to a wide range of pastoral groups rearing camel, sheep and cattle. The total number of animals in the state is estimated to be about 7.6 million heads. Pastoralism and smallholder crop farming are practised by the majority of the population in Gadarif State. Both pastoralism and smallholder crop farming are important components of the Sudanese economy and contribute to the livelihoods of a significant portion of the population. Livestock holds a prominent position in the nation’s economy, making a substantial contribution of approximately

60 per cent to the agricultural gross domestic product, constituing around 25 per cent of the overall national gross domestic product.

In Gadarif State, farmer-herder conflicts have intensified since the mid-1980s due to several factors, including climate change, land use policies favouring large-scale agriculture and, most recently, an influx of pastoralists seeking refuge from conflict in neighbouring regions. The refugee pastoralists are mainly from Blue Nile State. Conflicts primarily stem from competition for diminishing resources like land and water, particularly along livestock corridors and in forest resting areas.

Farmer-herder conflicts disrupt food production systems for both farmers and herders. Farmers face crop losses due to animal trespassing, leading to food insecurity and economic hardship. Herders, burdened by fines and restrictions on movement, experience reduced herd productivity and resort to alternative income sources like wage labour and crop cultivation. Despite the significant role played by pastoralism and smallholder crop farming in the food security of the country and its exports, policy-makers in Sudan often overlook their contribution. The primary rationale provided for the consolidation of authority is to facilitate the expansion of large-scale agriculture, with the belief that pastoralism and smallholder crop farming are antiquated methods of food production. Consequently, the state allocated land for large-scale mechanised farming.

Both farmers and herders prefer informal conflict resolution through traditional leaders because of its efficiency and cultural appropriateness. Thus, the ajawid is the main mechanism for resolving conflicts between the two groups in the area. Ajawid is a traditional mechanism for dispute resolution where respected members of the community and traditional leaders, usually male elders known for their knowledge of communal and customary norms, get involved to reconcile the parties through compensation or forgiveness without the involvement of the formal state authorities. This process is not time- or money-consuming, unlike the formal state methods.

While women and youth bear the brunt of the farmer-herder conflict impact, they remain largely excluded from conflict resolution processes. Farmer-herder conflicts are expected to worsen as resource scarcity intensifies and competition for land increases. The ongoing war in Sudan further exacerbates the situation by limiting pastoralists’ mobility and increasing livestock concentration in farming areas.

Hussein M. Sulieman, forthcoming.

Fiona Flintan is Senior Scientist at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and lead of the CGIAR Initiative on Livestock and Climate. She has worked on pastoral land issues and related issues for the last 20 years, mainly in East Africa. Contact: f.flintan@cgiar.org

Hussein M. Sulieman is the Director of the Centre for Remote Sensing and GIS at the University of Gadarif, Sudan. He is currently working as a consultant on pastoralism, land-grabbing, land tenure, land use and land cover analysis, and climate change.

Bedasa Eba is an Ethiopian Research Associate at ILRI based in Addis Ababa/Ethiopia. He has 14 years of experience in dryland ecology and management, rangelands and pastoralism.

Magda Nassef, an independent consultant currently working for ILRI, has spent nearly 20 years working in the Horn of Africa’s drylands, on pastoralism, land and natural resource management.

* With contributions from ILRI Consultants Georges Djohy, Kishmala Islam and Terry Earle.