Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

The scent of cinnamon and times to come

“This is our future,” says Hoang Thi Ton, holding up freshly peeled bark from a cinnamon tree. The inner bark is shiny and light caramel brown in colour. The essential oil it exudes is intensely fragrant and reminiscent of Christmas. In Hoang Thi Ton’s native Vietnam, cinnamon has been a staple cooking ingredient for centuries. Generations of ancestors flavoured their soups, sauces and pork ragouts with cassia cinnamon, which is extracted from the strong, oily bark of the trees of the same name. They are native to north-west Vietnam and neighbouring China.

Hoang Thi Ton’s home province of Yen Bai is the main growing area for cinnamon in Vietnam. One third of the province’s arable land is covered by cassia forests. According to the Vietnam Pepper Association, the hilly province produces roughly 18,000 tonnes of cinnamon bark and 85,000 tonnes of branches and leaves for essential oil production every year. Most of this is exported as raw material to more than 30 countries for further processing. The main customers are India, the USA and Bangladesh. The Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development announced a total export turnover of 292 million US dollars for the country in 2022, making the south-east Asian Socialist Republic the export champion and third largest producer of cinnamon in the world after Indonesia and China.

However, hardly any of the profits remain with the producers. Most of them belong to an ethnic minority and live in poverty. In Yen Bai, these smallholder farmers live off rice, maize and manioc as well as small livestock. They also earn a modest income by selling the wood, dried bark and oily leaves of their cinnamon trees to middlemen for little money. Whole families, from grandmothers to pre-school children, squat together in their front yards for days on end, painstakingly beating the bark off the branches with sticks. They receive the equivalent of less than one euro for a kilo of bark, and the hourly wage is even lower.

Many boys and girls drop out of school in order to supplement their family’s meagre income − and in doing so, they ruin their own future. But even with that extra money, their earnings are nowhere near enough to feed a family. Hoang Thi Ton wants to escape this poverty trap. To this end, she has replanted her parents-in-law’s two-hectare cinnamon hill in her village of Ta Lanh.

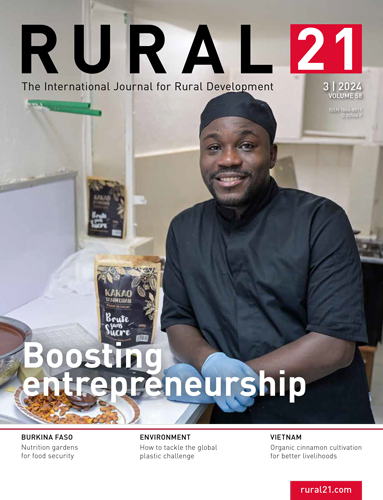

The bark of the cinnamon trees is used to make spices.

Striving for organic certification

“Our aim is to set up a cooperative in the community so that we can obtain organic certification for our products and market them more effectively,” says the 30-year-old smallholder farmer, who belongs to the Dao ethnic group. The neighbouring village of Nam Lanh has already modelled that approach. Colleagues there established a cooperative for certified bamboo shoots under the national VietGAP quality label. They are now expanding the brand in order to sell their bamboo shoots directly to restaurants, stable consumer markets and e-commerce platforms. At a later stage, they aim to preserve the raw materials themselves in order to increase added value. “Our goal is to do something similar with cinnamon,” says the dedicated young woman.

Then Hoang Thi Ton demonstrates how the precious and coveted spice is made. Together with her husband Ban Hui Phuc, she peels the straight trunk of a cassia tree that is roughly eight metres high and ten centimetres in diameter. “A tree has to be at least ten years old to be cut down,” explains the petite woman, whose hair disappears under the richly embroidered hat traditionally worn by the Dao women. “Our new plantations are still too young. We still have to wait a few years before we can cut them down.” Thanks to a project for the sustainable improvement of livelihoods, led by the semi-governmental women’s organisation Yen Bai Womens’ Union (YBWU) and international partners such as Brot für die Welt, they know that they should gradually remove the trees from the forest and plant new seedlings in their place in order to protect the soil from erosion, combat climate change and ensure a sustainable income. While her husband Phuc cuts into the bark with a sharp bush knife, she removes the bark from the trunk with a green plastic scraper. When Phuc can’t reach any higher up, he drives a wedge into the lower trunk. The tree crashes to the ground, where the young couple quickly continue their work. After three quarters of an hour, the entire trunk is bare and the bark and branches are piled up on the steaming forest floor. Drenched in sweat, the couple now look at a product worth a total of 200,000 Vietnamese dong. The middlemen pay just under eight euros for the raw material once it has dried in the sun. Hoang Thi Ton wants to significantly increase this value in the coming years through sustainable forestry, cooperative processing, certification and direct selling.

“The aim of this project is to increase the income of the people in the region and empower them to be drivers of their communities’ development,” explains Thuy Tran Thi in the new meeting house in the village of Ta Lanh, which the families planned and built themselves as part of the project. The YBWU sociologist coordinates the food project for some 4,000 people in seven villages in Yen Bai province. Almost all of the people here belong to ethnic minorities, and most of them are poor. They often lack not only knowledge, but also self-confidence. The village of Ta Lanh, with its 800 inhabitants, is a long way from the nearest main road. The closest town is half a day’s journey away. The YBWU team regularly visits the village to assess progress, answer questions and provide training in sustainable farming, forestry and livestock husbandry or hold workshops on village development. This afternoon, a course in integrated pest management (IPM) is on the agenda. Hoang Thi Ton will of course be there.

Dat Mai Van (r.) explains how to detect and control fungal diseases.

In the community hall, 32 men and women sit at long tables and consider problems and solutions. Only a few of them have completed more than primary school. Course instructor Dat Mai Van walks through the rows and explains how to control pests naturally. “Everything is interconnected,” he says. “You have to improve the soil, remove weeds, make compost, grow seedlings, remove worms by hand, make organic pesticides and spray the pests with them.” In the practical section that follows, he demonstrates how pest infestations and fungal diseases manifest themselves on the neighbouring plot. “What would you do with this?” he asks under a cloudy sky, holding up a brown-spotted cinnamon leaf. Hoang Thi Ton clears her throat and answers quietly: “We spray it with a mixture of garlic, ginger and chilli.” The course instructor nods approvingly, and the student breathes a sigh of relief.

Women move the community forward

“I never thought I’d be able to speak in front of a large group,” says the young woman later in her vegetable garden. “In our culture, women traditionally stay at home.” Hoang Thi Ton has been involved in the project since 2018, and for the past year now, has been a member of her village’s ten-person core team that works to improve the village infrastructure. She presents the development plans to local officials and authorities. “I want to make a difference,” says the open-minded woman, who has a flower tendril tattooed on her left forearm and operates her smartphone and scooter with ease. “The project gives me the opportunity to do that, and that’s brilliant.”

Her village community built the meeting house at the end of 2020. In the spring of 2023, they concreted a narrow road that runs right outside Hoang Thi Ton’s front door. It will soon get street lighting. “The road is a huge relief,” emphasises Hoang Thi Ton. “In the past, we often had to leave at three in the morning or even spend the night in our fields to work the land.” The Dao rice terraces are located above the village. It takes several hours to get there on foot, but only a few minutes by scooter or moped. Yesterday afternoon, when she got a call from a relative, Hoang Thi Ton was able to quickly drive to his field on her scooter. Together with 25 people, they managed to bring in the harvest before darkness and rain set in. “That wouldn’t have been possible without the road,” she remarks. Today, Hoang Thi Ton got up at five o’clock as usual, made breakfast, drove her eleven-year-old son Bao to school in 20 minutes, helped a neighbour with the threshing, cooked lunch, picked up Bao, cut down the cinnamon tree and took part in the seminar on top of all that.

But in the proud mum’s mind, the best thing is that thanks to the paved road her son no longer misses a day of school. “In the past, Bao had to stay at home for days on end when it rained because the roads were muddy and impassable.” The seventh-grader is her only child. “Children are costly. I want Bao to finish middle and high school and learn a proper trade or go to university,” Hoang Thi Ton explains. She is happy to work from early in the morning until late in the evening to make that possible. Not long ago, she and her husband had tried their hand at road construction in the harbour city of Haiphong as migrant workers. Bao stayed with her parents. “It was terrible,” says

Hoang Thi Ton. “It was awfully loud, dirty and crowded.” She earned 320,000 Vietnamese dong a day, not even 13 euros, with food and board provided for free. “We were homesick and missed Bao, the fresh air and the tranquillity of our village.”

Hoang Thi Ton is not yet a member of the bamboo cooperative, but she has the idea of setting up something similar in her village. “Maybe we can do it with our cinnamon,” she considers. Until then, she will continue to expand her organic vegetable garden. Next to the newly built house, she grows vegetables and herbs, sugar cane, sweet potatoes, manioc, bananas, avocado and guava trees. Her rice terraces cover the family’s own needs. She is now increasing her yields with organic fertiliser and sustainable cultivation methods. To cater for her future, she grows cinnamon seedlings as well as winter bamboo shoots, which after six months can be harvested in the same way as asparagus.

Next, she will submit an application for village lighting to the Women’s Union and the municipal administration. “Solar lights will make our streets safer in the dark,” says the enthusiastic project planner. “Then we can also meet in the evenings and do even more for our community.”

Constanze Bandowski is a freelance journalist and reports from Hamburg/Germany and around the world. Her main topics are development cooperation, sustainability, Latin America and social issues.

Contact: cobando@web.de

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment